[These blog entries are my notes and takeaways from Jonah Berger’s amazing book, The Catalyst as I apply them to Universal Healthcare.]

The Need for Freedom and Autonomy

Berger, Jonah. The Catalyst: How to Change Anyone’s Mind (p. 20). Simon & Schuster. Kindle Edition.

Example 1: anti-smoking campaign based on telling teenagers not to smoke backfired. Same with the tide pod ad campaign with Grabowski. Simply telling people does not work. They push back-reactance.

What does work is amplifying freedom and autonomy. He uses the example of a nursing home where residents get more choice in their living arrangements and activities.

HCR Lessons:

Telling people that single-payer or some other solution is the correct answer will not work. It creates reactance. For me, I have thought for more than a decade that the solution is to provide people with memorable examples of excellent healthcare in other nations. This is based on the prospect theory ideas of recency and availability. Currently, when people are engaged about universal healthcare, recency and availability leads them to think of long wait times and rationed care. That is no accident. Conservatives have spent years and tons of money making it that way. They have a few choice anecdotes about sad stories of individuals in Canada or the UK and they can trot them out endlessly. They never get old, they reinforce what conservatives have been reinforcing for decades and so positions harden, rather than soften when we present examples of good care and other nations.

We have not done the groundwork to make the excellent care available in other nations recent and available. We need to do a lot of work showing how the choice is not between healthcare in a Soviet Gulag and the current mess we have now, rather it is between the current mess we have now and universal, simple, and affordable healthcare without wait times without the hassles and far cheaper.

We can further expand in this area by making clear that what we want in our freedom and autonomy is not which commercial health insurance plan we get to choose from-the lesser of a 1000 evils-but freedom to choose our doctors and hospitals and be the captain of our healthcare ship.

Prior authorization is freedom denied. High out-of-pocket expenses are freedom denied. Spending countless hours dealing with bills and explanation of benefit forms and appeals and the whole mess is freedom denied. Et cetera, the examples are endless. (BTW, we put together a piece in response to Frank Luntz’ 2009 guide to talking down the ACA, and it is pretty good along these very lines of thought.)

He points out that people are loath to give up agency. They have been told for decades that having employee-based health insurance is somehow agency. I think the experience of most of us with employer-based health insurance is anything but an exercise in autonomy. How many hours have we as individuals and as a society devoted to choosing among multiple health plans from our employer every year? If there were a choice that included near-complete coverage, minimal out-of-pocket expenses, no lifetime limits, unlimited choice of doctors and hospitals and basically what most citizens of developed nations expect as a given, who would not make that choice? Instead, our agency is to choose among the “cream of the crap,” as Paul O’Neill would say.

Reactance and the anti-persuasion radar.

People often take contrary position because they feel like they are being asked to do something. Not even commanded, just asked. People will even resist initiatives that they themselves wanted simply because they become mandatory or imposed in some way. Avoidance is the most common defense mechanism-simply ignoring the message. If they cannot avoid the message, they will cognitively shoot down every component of the message including content and source.

HCR lessons:

This is tough in these highly partisan times. Having content and sources that can at least partly tear down the barriers may end up being key. That is why I think that pairing doctors and nurses to deliver these messages might be key. Doctors are generally trusted, and nurses even more so. And as his corroborating evidence chapter discusses later on, having multiple sources from different areas is more powerful than, say, 5 doctors from PNHP.

Allow for Agency

Important discussion here about getting the perspective of the target audience. He uses the antismoking campaign example and tells how the team asked teenagers for their perspective on the antismoking campaign. They let the teens themselves craft the messages and in this case the messages of tobacco industry manipulation of the public and the political system. “Here is what the industry is doing, they said. You tell us what you want to do about it.”

HCR lessons:

Clearly this can be a powerful tool. We know what the medical industrial complex has been doing for decades. We can craft the messages straight out of Elizabeth Rosenthal’s An American Sickness, chapter by chapter!

I love the example of creating workbooks showing, exactly as Katy Porter did with Revlimid, exactly how pharmaceutical pricing impacts executive pay. (I think it would be also a fun exercise to show how that pricing translates into bonuses for the workers at the company, particularly the scientists who actually do the beneficial work in the industry.)

The other example about the teenagers calling out the magazine executive about not running anti-smoking ads as a public service practically writes itself when translated into healthcare. “Is this about people or about money?”

Berger notes that this campaign worked because it did not tell teenagers to stop smoking, it gave them information from their peers, and they were given agency to make a decision. This encourage them to be active participants rather than passive bystanders, Berger notes.

Creating agency reduces reactance and allows room for action. I can see campaigns pointing out the exorbitant costs of insulin or other medications, the “financial toxicity” of illness, and allowing the public to make up its mind about the acceptability of all this. Of course, there are thousands of other examples that doctors and nurses and health policy experts can give to create ads.

Four key ways to do that are: (1) Provide a menu, (2) ask, don’t tell, (3) highlight a gap, and (4) start with understanding.

Provide a Menu: Let them choose how they get where you are hoping they’ll go.

Provide the trade-offs upfront, as when negotiating salary versus paid time off in Berger’s example. Or, as one selecting off a menu at the restaurant-you are limited to what is on the menu, but there are still many choices. Or offering multiple choices of direction to a client when pitching something. Getting to choose between multiple options reduces reactance.

HCR lessons:

This is why I still I think the single-payer movement is doomed. It presents a single choice as the best choice and only choice.

Ask, Don’t Tell

The example here is a good one about asking students about their expectations of the hours required to prep for a GMAT exam. Basically, this is allowing for an interaction that lets the student figure out, by providing information and feedback, a more realistic study schedule.

This shifts the student from reactance and thinking of all the reasons to disagree or discount the information, the student becomes actively trying to figure out a real answer. Their opinion is valued.

Being able to ask questions increases buy-in. Asking questions that inform their thinking makes them participants in creating the best answer for them.

Berger writes that questions encourage listeners to commit to the conclusion. Asking the question framed around the student’s goals allowed them a path to the solution.

HCR lessons:

I went to the Mob Museum in Las Vegas a couple years ago. One of the things that caught my attention was the Kefauver commission. Sen. Kefauver went around the country holding hearings on organized crime and the effects on the communities he was visiting. This did 2 things. It raised awareness and humanized the crimes. They were no longer ephemeral.

When I was reading the section, I couldn’t help but think how powerful it would be to do sessions around the country with the goal of highlighting the negative effects of the medical industrial complex on ordinary people and then giving them the chance to ask questions of knowledgeable doctors and nurses about potential solutions. For me, this must be people knowledgeable about international healthcare systems. I think the answers are out there and we simply refuse to look for them. Having knowledgeable people be able to answer questions about how we solve X problem and being able to offer a tried-and-true international example would be powerful.

“It is a mistake for any nation to merely copy another; but it is even a greater mistake, it is a proof of weakness in any nation, not to be anxious to learn from one another and willing and able to adapt that learning to the new national conditions and make it fruitful and productive therein.” – Teddy Roosevelt.

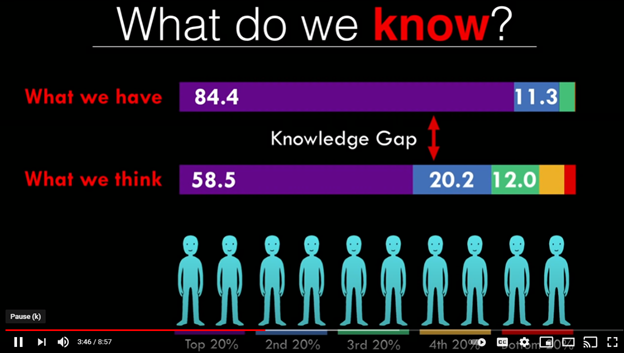

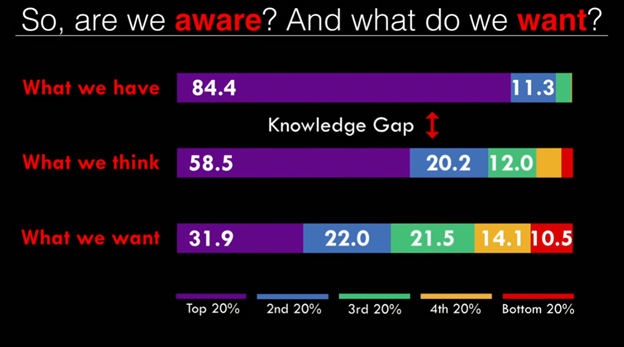

Highlight a Gap: show the disconnect between what we do or think versus what we might recommend to others.

The important example in this section is about killing off something that is ongoing. He uses the example of a project within a business that is being proposed at the current moment would not be started, but as an existing ongoing project, it is hard to kill it. He attributes this to inertia and somewhere in another chapter he does talk about status quo bias and endowment.

HCR lessons: clearly this should be an important strategy for healthcare reform. I think there are very few people, conservative or liberal, who would create the US healthcare system as it is if they were designing a system from scratch. Some conservatives might argue for at least some of the pro-business, pro-market portions, but very few would argue to keep the system even close to what it is. And pulling confirms this, with a large majority of Americans thinking the system needs to be rebuilt entirely or have major changes. The cost of doing nothing in “blood and treasure” is enourmous.

Start with Understanding.

“Before people change, they have to be willing to listen.”

You cannot start a discussion jumping immediately to the outcome you want and expect people to come along. You must listen to them and understand them first. This requires understanding the other person, gaining insights appreciating their situation. Start by building a bridge.

Tactical empathy allows for not only showing compassion, it also allows one to gain valuable information. Using phrases like you and I, using us and we while working out and working towards solutions is of great value.

It is helpful if by using these techniques the other person feels as if the solution was their idea, or at least partly their idea. (Similar to the GMAT example.)

The other example he gives is not about a hostage situation, but about a suicidal father. The key here is pointing out to him his actions’ effect on his kids. “When people feel understood and cared about, trust develops.”

HCR lessons:

of course, these ideas are powerful in dealing with individuals, but I would circle back around to the Kefauver commission type events. Imagine talking to members of the audience, learning their concerns and developing trust. (As I am brainstorming this, I imagine some truly great ads could come out of the recordings of these sessions!)

Understanding their fears and concerns about transitions to universal healthcare are key. Just like in the Kaiser surveys, when asked about universal healthcare support is two thirds. Add to the question that one would lose one’s employer-based insurance, the support drops in half. This is natural, it is loss aversion. We need to understand the concerns of someone who has employer-based insurance and their fears. We need to allay those fears. We need to understand and offer solutions. In the case of developing a good universal healthcare system, the upsides are protean if you are aware of them. If not, you just think of care delayed and care denied. And, as part of my theme about our vast moral gap on these questions, transitioning to support of universal healthcare means letting other people “get over on you.” (A discussion for another article.)

There’s a Mark Twain quote, “Compassion is such a basic human emotion that it has even been observed among the French!” In spite of the fear of many of having other people get over on them, people are also generally compassionate. Uwe Reinhardt says something along the lines of “Americans are capable of both magnificent generosity and unfathomable cruelty.” The idea of talking about our children and our community’s children and their community’s disabled and poor and so on might be powerful. It would make for some interesting testing, but, it would be consistent with Kalla and Brickman and the deep canvassing techniques covered later in the book.

Berger, Jonah. The Catalyst: How to Change Anyone’s Mind (p. 83). Simon & Schuster. Kindle Edition.