Along my journey in Cognitive Science I came to discover Dan Ariely, and then came across a TED talk he gave called How Equal Do We Want To Be? He explores economic inequality and what we think we know about economic inequality, the reality of income inequality and finally what we would like income inequality to be. I think there are important correlations to how equal do we want to be in healthcare, and brought this here for discussion.

You can easily skip my summary of his talk and just go over and watch it, but I also wanted to capture some of the graphics, as I think with just a little imagination, they can be transformed into important questions about our healthcare system!

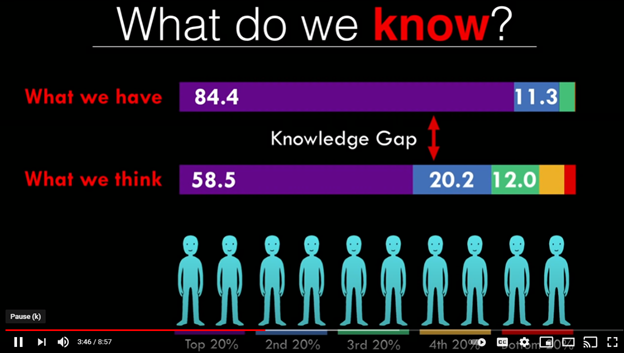

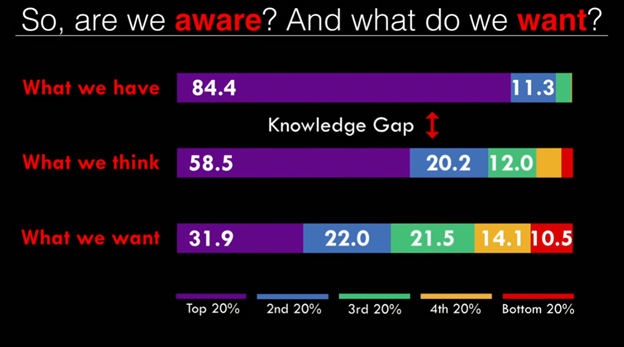

So, from the top! What we think is that the top 20% have 58.5% of the wealth and the bottom 40% have about 10% of the wealth.

In reality, the top 20% have 85% of the wealth the next 20% have 11% in the bottom 60% share the last 5%. He calls this difference between what we think and reality the Knowledge Gap.

Along those lines, he asks what we think the pay ratio of CEOs is to that of unskilled workers. He shows this graph showing what people think it is (Estimated), when it actually is (Actual), and our ideal notion.

Not so bad, right? Oops, he didn’t adjust the scale. Here’s the reality.

We are in Alice in Wonderland territory now. But if you are in the CEO or top 20%, it’s a very happy Wonderland, indeed!

During the talk, Ariely references John Rawls and his theory of distributive justice. He asked whether, if we could design our system, would we choose what we have? So he asks, “How should the wealth be distributed?”

Quite a different picture! The fairness is striking! Sure, those at the top do better, but those at the bottom should not be destitute, either. He calls this difference between what we think we have and what we want the Desirability Gap.

His last step is to ask us not only what do we think we know and what do we want, but what are we going to do about it? This is the Action Gap. There is much activity in the action gap of late. (Well, maybe Bernie Sanders not just lately.) But the recognition of massive wealth inequality finally seems to be making it into mainstream debates on policy in America for the first time in decades.

I will leave that larger societal question to others. My lane is the healthcare line, particularly the fairness of healthcare lane, or the social justice Lane. Ariely notes that he has done research about other areas of inequality including health, availability of prescription medications, life expectancy, infant mortality, and education. He notes that we are even more averse to inequality in these areas than we are regarding wealth. We are even especially averse to inequality when the individuals have less agency, like children. (I would be interested in extending my research to see if it also applies to people born into all lower social economic statuses.)

I do not know if there is research on what Americans think about the injustices or performance of the US healthcare system. I do know that most Americans know that we are not the best and no favor major changes or complete overhaul of the system. And of course, we do know many of the realities. We know we spend far more than any other nation and do not cover everyone. We know we have very high out-of-pocket costs. We know we have relatively low life expectancy and high infant mortality. We know our citizens are less likely to survive serious illnesses. We know that we have less physicians and our people see our physicians less frequently than other nations.

At a baseline, we do not even know what The US Healthcare Knowledge Gap is. We do not know what the public does not know. That makes it hard to get to the Desirability Gap, let alone the Action Gap.

Can we get by without knowing what the Healthcare Knowledge Gap is? Maybe. But it will be nearly impossible to move forward without knowing the Desirability Gap.

This will take some serious work. Not only do we need to do the work to educate people on the reality of American healthcare, we then have to do research to find out what we,or at least what most of us, want to do. After decades of watching progressives telling people that what they should want is single-payer, I know that telling people what they want is not the answer. We need to do some work and we need to have some conversations and we need to come up with solutions.