The opportunity exists to deliver more services and care with fewer physicians, but it’s not a foregone conclusion. Policy changes will be necessary to reach the full potential of team care.

That means expanding the scope of practice laws for nurse practitioners and pharmacists to allow them to provide comprehensive primary care; changing laws inhibiting telemedicine across state lines; and reforming medical malpractice laws that force providers to stick with inefficient practices simply to reduce liability risk. New payment models must reward investments in technologies that can save money in the long run. Most important, we need to change medical school curriculum to provide training in team care to take full advantage of the capabilities of nonphysicians in caring for patients.

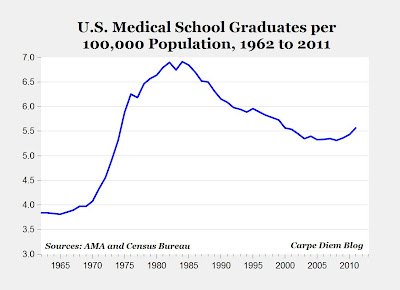

Instead of building more medical schools and expanding our doctor pool, we should focus on increasing the productivity of existing physicians and other health care workers while incorporating new technologies and practices that make care more efficient. With doctors, as with drugs or surgery, more is not always better.

Scott Gottlieb, an internist and fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, was a senior official at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services during the George W. Bush administration. Ezekiel J. Emanuel, a former health policy adviser to the Obama administration, is an oncologist, vice provost at the University of Pennsylvania and contributing opinion writer.